How much can you learn from a microscopic drop of ancient seawater? More than you might think, a new study shows. Researchers have analysed a series of such drops and arrived at an estimate that the process that underpins Earth's plate tectonics may have started some 600 million years earlier than previously thought.

Plate tectonics – the constant movement of huge blocks of Earth's crust – is a crucial part of the renewal of our planet's surface, and may even be essential in enabling life to flourish.

By analysing levels of H2O and other molecules in microscopic "melt inclusions" caught in volcanic rock samples known as komatiites, researchers have come up with a new timeline for when seawater started getting pushed down from the surface into the mantle – the point when convection started occurring in Earth's mantle.

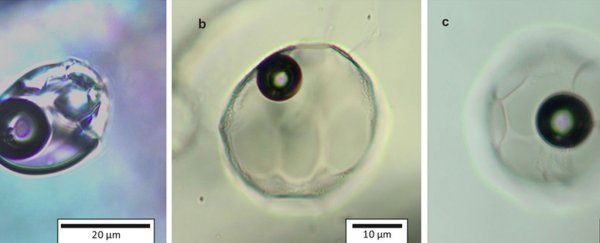

Olivine-hosted melt inclusions studied by the team. (Sobolev et al., Nature, 2019)

Olivine-hosted melt inclusions studied by the team. (Sobolev et al., Nature, 2019)

The team was able to analyse the ancient water droplets because they'd been captured by the mineral olivine, found in komatiites from the Komatiite lava flow the rocks are named after – left behind by the hottest magma ever produced in Archaean Eon (4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago).

"The mechanism which caused the crust that had been altered by seawater to sink into the mantle functioned over 3.3 billion years ago," says geologist Alexander Sobolev from the Russian Academy of Sciences.

"This means that a global cycle of matter, which underpins modern plate tectonics, was established within the first billion years of the Earth's existence, and the excess water in the transition zone of the mantle came from the ancient ocean on the planet's surface."

The shifting of Earth's plates and mantle has an effect on everything from atmospheric conditions to the minerals deposited underground, as well as the earthquakes and volcanoes you might usually associate with tectonics.

"Plate tectonics constantly recycles the planet's matter, and without it the planet would look like Mars," says geoscientist Allan Wilson, from Wits University in South Africa.

"Our research showing that plate tectonics started 3.3 billion years ago now coincides with the period that life started on Earth. It tells us where the planet came from and how it evolved."

The geological landscape formed by these tectonic movements also provides an excellent record of what's happened in the past, which the researchers have tapped into here. The komatiite they dug up was taken from the Weltevreden Formation in the Barberton greenstone belt in South Africa.

"We examined a piece of melt that was 10 microns [0.01 mm or three-ten-thousandths of an inch] in diameter, and analysed its chemical indicators such as H2O content, chlorine and deuterium/hydrogen ratio, and found that Earth's recycling process started about 600 million years earlier than originally thought," says Wilson.

"We found that seawater was transported deep into the mantle and then re-emerged through volcanic plumes from the core-mantle boundary."

(Wits University)

(Wits University)

The chemical signature of the analysed rocks matches the lithospheric mantle – the uppermost part – from the Archaean, despite coming from further down in what's known as the transition zone between the upper and lower mantle.

That komatiites were able to grab so much water from so deep underground before being shot up to the surface suggests the plate tectonics cycle was happening earlier than 2.7 billion years ago – the current accepted starting point.

With so many variations to account for in terms of chemical mixes, pressure, and geological processes, more research is going to be required to figure out exactly when material in Earth's crust and mantle first started shifting – but it could well have been happening for longer than we thought.

The research has been published in Nature.