Decades before we marched in protest over the growing climate crisis, a giant hole in the ozone layer demanded our attention. It's a good thing we acted on it, too – without the changes that followed, our future would be looking even hotter.

Thanks to regulations on emissions of ozone-destroying class of greenhouse gas called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), projected global temperatures for 2050 are at least one degree Celsius cooler than what they might have been otherwise.

That one degree is far from trivial, not when a projected rise of just two degrees in coming decades could return us to a climate that hasn't been seen in several million years, along with a host of devastating consequences.

Researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Australia, have evaluated various climate scenarios using simulations combined with a global climate model to judge what our planet might look like if the 1989 Montreal Protocol had never taken place.

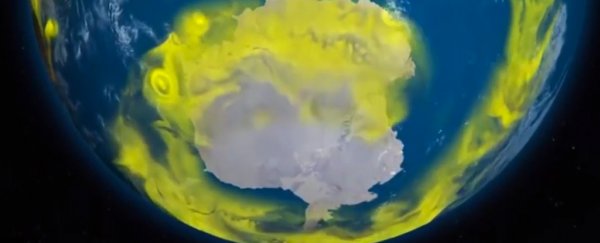

Their initial goal was to see how a drop in ozone-depleting chemicals affected atmospheric circulation around the Antarctic. They imagined a world where CFCs continued to build at around 3 percent each year – a rate that's rather conservative given increasing demands of the material towards the late 20th century.

It's a world we can be grateful we no longer live in.

Ozone is an oxygen molecule that absorbs certain wavelengths of light in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum. Its density in the atmosphere increases slightly 20 to 30 kilometres (12 to 19 miles) up overhead, forming a layer that helps to protect the biosphere from the damaging effects of this radiation.

Industrial quantities of ozone-damaging compounds pumped into the atmosphere throughout the early to mid-20th century already had a devastating effect on this shield, especially over the bottom end of the globe.

What was basically a thinning out of ozone was famously described as a hole, one that the world rallied to fix.

In 1985, world leaders came together to sign the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, a promise that would later take the form of a protocol designed to phase out the production of ozone-destroying chemicals around the world.

Three decades later, the gap in a protective section of the atmosphere has all but vanished. (Watch the clip by the Australian Academy of Sciences below for a 101 on the topic.)

It's a success story worth celebrating. In spite of a handful of rogues still pumping out pollutants, the protocol signed in Montreal is now regarded as a perfect example of what humanity can achieve when it puts a sustainable future ahead of business profits.

Now we have solid data showing the protocol had another big benefit.

"By mass CFCs are thousands of times more potent a greenhouse gas compared to CO2, so the Montreal Protocol not only saved the ozone layer but it also mitigated a substantial fraction of global warming," says climate scientist Rishav Goyal from UNSW.

This is especially great news for our poles. If not for taking action on the ozone hole, those greenhouse gases would have ended up pushing Arctic temperatures up by as much as 4 degrees by mid this century.

The summer ice around the North Pole isn't exactly what it used to be. But by the researchers' calculations, there's 25 percent more of it now we've done away with CFCs.

Take a brief moment to sigh with relief. But as we all know, there's still plenty of work to do.

"Montreal sorted out CFC's, the next big target has to be zeroing out our emissions of carbon dioxide," says oceanographer and climate scientist Matthew England, also from UNSW.

Merely calling for another Montreal-like agreement isn't going to cut it this time, either.

The Kyoto protocol has a far lower bar in some ways – aiming to reduce temperatures by just a fraction of a degree by 2050 in an attempt to limit catastrophe.

But the task ahead of us is unlike anything we've seen before. Compared to our taste for ozone-depleting chemicals, our hunger for fossil fuels is ravenous.

The stakes have never been greater. If there are lessons in the history of global politics, now is the time to learn from them.

"The success of the Montreal Protocol demonstrates superbly that international treaties to limit greenhouse gas emissions really do work; they can impact our climate in very favourable ways, and they can help us avoid dangerous levels of climate change," says England.

This research was published in Environmental Research Letters.