The growing problem of antibiotic resistance – superbugs hardened against our best drugs – already claims tens of thousands of deaths a year, but new research suggests an unlikely ally is ready to help us in our fight against the threat: insects.

We've traditionally mined the bacteria in soil for the source of our antibiotics, but now that well is running dry, scientists think the microbes in tiny soil particles attached to insects might give us a brand new source of infection protection.

Every insect hosts a miniaturised ecosystem of microbes, which are constantly battling each other – the toxic compounds that they develop to try and survive are essentially natural antibiotics, and if we can extract them then we have a very promising route to developing new medicines for our own use.

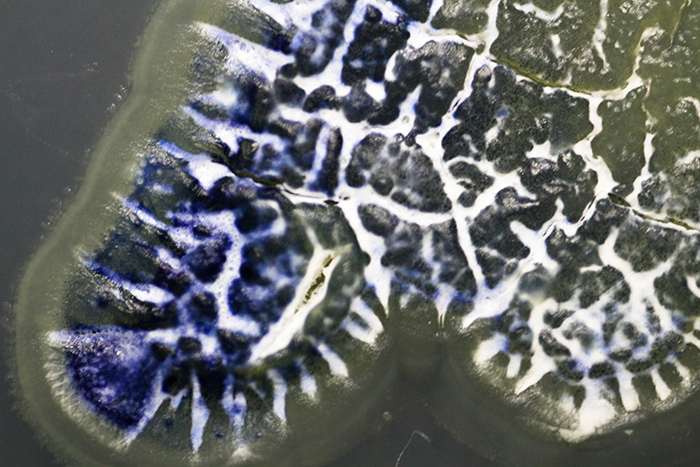

Streptomyces bacteria (purple) that produces cyphomycin. (Caitlin Carlson)

Streptomyces bacteria (purple) that produces cyphomycin. (Caitlin Carlson)

In an analysis of microbes from more than 1,400 insects collected across North and South America, an international team of researchers discovered that the microorganisms carried by these little bugs were often more effective than soil bacteria in stopping some of the most dangerous, antibiotic-resistant pathogens we know about.

"Novel therapeutics are needed to counter resistance, yet no new antimicrobial classes have been clinically approved in over three decades," explains the team.

"The extreme diversity of insects presents untapped potential for drug discovery from their equally diverse microbial communities."

The researchers particularly focussed in on the Streptomyces class of bacteria, responsible for giving us many of the antibiotics in use today.

The way this bacteria has evolved in its association with insects gives us a "new chemistry" separate from what we have in soils, the scientists say.

"The insects are doing the prospecting for us," says senior researcher behind the study, bacteriologist Cameron Currie from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

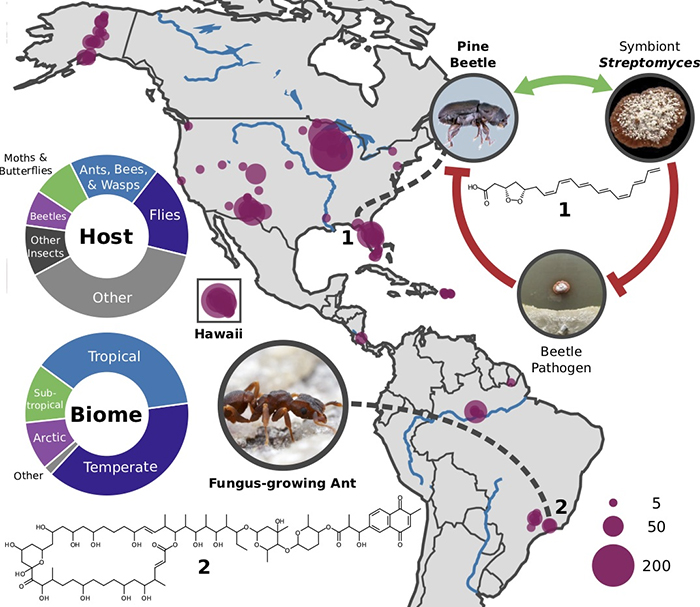

Some of the collection data from the study. (Cameron Currie/Marc Chevrette)

Some of the collection data from the study. (Cameron Currie/Marc Chevrette)

And once the insect microbes had been identified, the testing was exhaustive – more than 50,000 trials were undertaken to see how each microbe worked to stop the growth of 24 different types of bacteria and fungi.

Ultimately the experiments showed more of the insect microbes were able to stop bacteria and fungi growth than microbes isolated from soil and plants – and that gives us an exciting new avenue to explore in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

Once a bacteria strain that can kill off germs has been found, further analysis is needed to work out which compound is doing the work before a drug can be made.

That can take years, and isn't always guaranteed to succeed, which is why scientists want as many potential candidates as they can get at the early stages.

The research has already turned up a promising new antibiotic though, which has been given the name cyphomycin. It proved effective against fungi resistant to most other antibiotics, and even removed fungal infections with little effect on the mice themselves.

That's really good news, but even so, cyphomycin is a long way from being available as an actual drug. It is however more evidence that we can potentially produce antibiotics from these busy microbe communities living on insects.

"The promise of insect-associated Streptomyces as a new source of antimicrobials has the potential to reinvigorate the stagnated antibacterial and antifungal discovery pipelines," conclude the researchers.

The findings have been published in Nature Communications.