Fears that our immune system could swiftly forget its encounter with the SARS-CoV-2 virus are increasingly unfounded with an Australian study revealing our blood is still capable of mounting a strong response eight months post-infection.

This is good news for those concerned that COVID-19 vaccines won't deliver the period of protection needed to manage the virus's spread throughout the population.

"This has been a black cloud hanging over the potential protection that could be provided by any COVID-19 vaccine and gives real hope that, once a vaccine or vaccines are developed, they will provide long-term protection," says Monash University immunologist Menno van Zelm.

While it's still too early to tell just how long immunity to this specific coronavirus might last, we can be confident time will probably be on our side.

In a collaboration between Monash University, The Alfred Hospital, and the Burnet Institute in Melbourne, researchers analysed blood samples taken from 25 volunteers diagnosed with COVID-19.

Each sample provided a snapshot of the immune system's status, from just four days after infection to as long as eight months.

A further 36 individuals with no history of the disease also provided one or two blood samples for comparison.

The COVID-positive samples suggest concentrations of free-floating SARS-CoV-2 antibodies begin to fade just 20 days after symptoms appear, a finding that falls in line with previous studies suggesting antibody levels drop quickly, especially in mild cases of COVID-19.

While this isn't in itself surprising, it has caused consternation among immunologists over whether we should expect waves of reinfections in coming years.

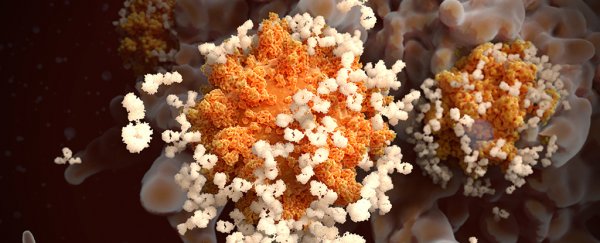

Antibodies are like mug-shots for the immune system, allowing it to pounce readily on past offenders who dare to show their face again. Without them, it's far too easy for a past infection to waltz right back in.

In the case of some pathogens, these chemical 'wanted' posters stick around for years. Measles, for example, provokes an antibody response that barely drops throughout your lifetime.

Other agents of disease fade from memory a little faster. For tetanus this vanishing act takes just over a decade, requiring frequent reminders in the form of booster vaccines to nudge the system into printing out a fresh batch of antibody 'mug shots' all over again.

The key to this antibody-printing service are white blood cells called memory B cells. Formed during an infection to print out antibodies specific to an invader, these cells can hide away for decades once the heat dies down, ready to generate a fresh supply of antibodies at a moment's notice if the pathogen were to reappear.

To see whether a COVID-acquainted immune system still had sufficient B cells to do the job after just a few months, the researchers introduced fluorescently labelled pieces of SARS-CoV-2 to the once-infected blood samples.

The analysis not only revealed a significant response in each of the COVID-19 blood samples, but allowed the team to determine which kinds of B memory cells were reacting to which particular chunk of the virus's body.

"These results are important because they show, definitively, that patients infected with the COVID-19 virus do in fact retain immunity against the virus and the disease," says van Zelm.

And since the proteins analysed by the study are considered prime sites to target, we can expect most vaccines will also convey a good level of immunity for at least eight months.

Beyond that? Time will tell. Hopefully we can bring news in coming years of continued immunity that lasts well beyond expectations.

For the pandemic to be brought well under control, if not eradicated altogether, we'll need at least 70 percent of a population to be immune within the same window of time. Only then can we be sure the virus will have so few places to hide, it just might vanish.

Right now we can be fairly sure that window is eight months wide. Let's hope it's enough.

This research was published in Science Immunology.