In another context, Jupiter's moon Ganymede might have been a planet.

As the largest moon in our Solar System, it's one of the most intriguing locations in the neighborhood. Which is great, because it just so happens that Jupiter probe Juno is in the vicinity. Now, it's sent back some curious noises.

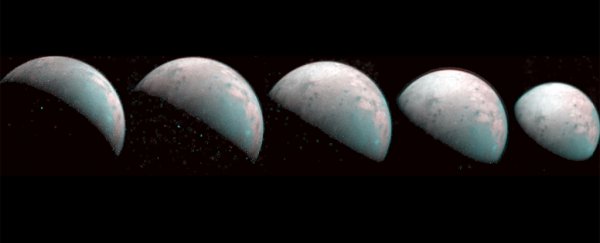

On 7 June 2021, Juno conducted a close flyby of Ganymede, and recorded the moon's electromagnetic waves – electric and magnetic waves produced in the magnetosphere – with its Waves instrument.

When the frequency of these emissions is shifted into the audio range, the result is a wonderfully eerie set of alien shrieks and howls. This audio was unveiled at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting 2021.

"This soundtrack is just wild enough to make you feel as if you were riding along as Juno sails past Ganymede for the first time in more than two decades," says physicist Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute, Juno's principal investigator.

"If you listen closely, you can hear the abrupt change to higher frequencies around the midpoint of the recording, which represents entry into a different region in Ganymede's magnetosphere."

Transposing the data into audio frequencies isn't just for fun; it's a different way of accessing and experiencing the data, which can in turn help to pick up on fine details that otherwise might have been overlooked. We've been recording the "sounds" of the Solar System with a range of probes, including the Voyager spacecraft, as well as planetary missions.

Ganymede – which is even bigger than Mercury – has a fully differentiated core, and might have a liquid ocean deep beneath its icy crust that could support life. On top of all that, it has its own magnetic field, the only one of the Solar System's moons to have one.

The Galileo spacecraft, which studied Jupiter in the 1990s and early 2000s, also sampled the space around Ganymede, leading to the revelation that plasma waves are a million times stronger around the moon than the median activity at corresponding distances around Jupiter. It's unclear whether that has anything to do with the moon's magnetic field, but it seems likely.

Juno flew down as low as 1,038 kilometers (645 miles) from the moon's surface, at a relative velocity of 67,000 kilometers per hour (41,600 mph). What the new data will reveal is a work in progress, but scientists already have a few ideas.

"It is possible the change in the frequency shortly after closest approach is due to passing from the nightside to the dayside of Ganymede," says physicist and astronomer William Kurth of the University of Iowa.

Of course, the new discoveries were not confined to Ganymede. Juno has also been busily taking observations of Jupiter, obtaining the most detailed map yet of the gas giant's magnetic field. This map has taken 32 orbits to compile, and has provided new insights into the equatorial magnetic anomaly known as the Great Blue Spot.

The data suggest Jupiter's magnetic field has undergone a change in the last five years, and that the Great Blue Spot, being pulled apart by the powerful Jovian winds, is moving eastward at four centimeters per second relative to the rest of the planet's interior. This suggests it completes a lap every 350 years.

Because a planetary magnetosphere is produced by a dynamo in the planet's interior – a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid that converts kinetic energy into magnetic energy – studying a magnetic field allows scientists to understand that dynamo. The team's new map suggests Jupiter's dynamo is generated by a deep layer of metallic hydrogen surrounding its core.

Scientists also studied the Juno data to understand turbulence in the Jovian atmosphere. The similarity of this turbulence to the turbulence of phytoplankton in Earth's oceans led oceanographer Lia Siegelman of Scripps Institution of Oceanography to try and connect the dots. She learnt that, on Jupiter, patterns of vortices form spontaneously and will hang around long-term.

(NASA OBPG OB.DAAC/GSFC/Aqua/MODIS/NASA/JPL/SwRI/MSSS/Gerald Eichstädt)

(NASA OBPG OB.DAAC/GSFC/Aqua/MODIS/NASA/JPL/SwRI/MSSS/Gerald Eichstädt)

Above: Plankton bloom on Earth compared to the clouds of Jupiter.

Finally, the researchers unveiled a new photo of something rarely seen: Jupiter's tenuous main dust ring, associated with dust released by its moons Metis and Adrastea. Juno imaged the structure from inside the ring, looking out into the stars, capturing the arm of the constellation Perseus.

Jupiter's ring. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Jupiter's ring. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

"It is breathtaking that we can gaze at these familiar constellations from a spacecraft a half-billion miles away," says astronomer Heidi Becker of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"But everything looks pretty much the same as when we appreciate them from our backyards here on Earth. It's an awe-inspiring reminder of how small we are and how much there is left to explore."

Juno's extended mission will run until June 2025, and is expected to continue to provide amazing insights into our Solar System's complex, weird and wonderful colossus, Jupiter.

The results were presented at the AGU Fall Meeting 2021.