NASA has announced that Mars' Gale Crater, the landing site of the Curiosity rover, once held a lake that existed for millions of years - potentially long enough for life to have formed.

Scientists already suspected that the Gale Crater once held water and the "right ingredients and environment to have been able to support microbial life," said Michael Meyer, the lead scientist of the Mars Exploration Program in a teleconference on Monday afternoon in the US, as The Verge reports.

But up until now, researchers weren't sure how long these conditions had lasted.

The new results show evidence that multiple cycles of water would have flowed into a huge, shallow lake that could have lasted tens of millions of years. The time-frame would potentially have been long enough to seed life on the planet.

The results also suggest that it was the pattern of this water flow over millions of years that formed Mount Sharp, or Aeolis Mons, which towers at 5 km in the middle of the crater.

"If our hypothesis for Mount Sharp holds up, it challenges the notion that warm and wet conditions were transient, local, or only underground on Mars," said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity deputy project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, in a press release.

"A more radical explanation is that Mars' ancient, thicker atmosphere raised temperatures above freezing globally, but so far we don't know how the atmosphere did that."

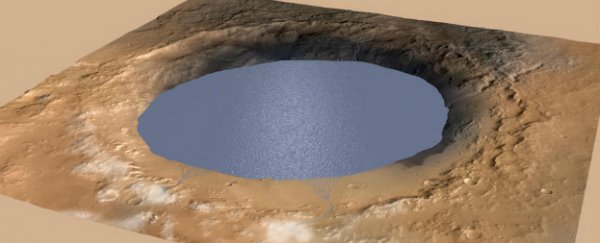

Gale Crater is more than 150 km (96 miles) in diameter, and NASA has now released an illustration (above) of what the huge lake that once filled it may have looked like.

The discovery was made after Curiosity took images of and analysed the sediment layers in the crater, and compared them to lake formation here on Earth. The patterns of layer formation show evidence of multiple cycles of rivers and deltas moving across the crater over millions of years.

Curiosity landed in the Gale Crater in 2012, and has since been making its way towards Mount Sharp, where it arrived in September and has been analysing drilling holes and analysing sediment ever since. The rover's primary mission is to find out whether Mars could have hosted life.

The results now show that the Gale Crater was once filled with a lake that dried up but then reappeared several times, laying the sediment that formed Mount Sharp.

But one of the most important implications of this research is what it tells us about Mars' climate - the Red Planet currently has all of it water frozen into polar ice caps, but the new results suggest that at some point its climate system was "loaded with water", as Vasavada explained in the conference.

"The humidity could be explained by expanses of warmer ice at lower latitudes, or even better — by expanses of liquid water, like an ocean," said Vasavada, as The Verge reports.

Another possibility is that the lake could have come and gone in response to short-term climate cycles, potentially caused by volcanic activity or crater impacts.

"The question is, could temporary climate fluctuations form what we see geologically, or do we need longer term warm wet climate?" as Vasavada explained in the conference.

All of this is something that NASA already suspected, but couldn't prove from orbit. The next step is to continue drilling into the sediment in the foothills of Mount Sharp and taking images of the sediment patterns left behind by what we now know was once a gigantic lake.

As Sean O'Kane reports for the Verge, Curiosity's journey from landing to Mount Sharp so far has been long, but worthwhile.

"All that driving we did really paid off for science. It didn't just get us to Mount Sharp, it gave us the context to appreciate Mount Sharp," said project scientist John Grotzinger in the conference.

We can't wait to see what Curiosity unearths next. This is probably as good a time as any to re-watch It's Okay To Be Smart's inspiring "Ode to Curiosity".

Sources: The Verge, New Scientist, NASA