As far as years go, you could do a lot better than 536 CE. By some historians' standards, it may have well been 'the worst year to be alive in human history'. Depending on where a person lived around the globe, those cold, bleak times kept on truly sucking for many years to come.

Now, it seems it might not have been the worst thing, at least for the Ancestral Puebloan communities who occupied the southwestern US. In fact, the darkness of this brief, global ice age might have heralded a bright new day for their culture.

A study conducted by a team of archeologists and anthropologists from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and Colorado State University in the US has uncovered signs that the population spread across the Four Corners region not only recovered from a catastrophic climate shift in the mid-6th century – in some ways they came back stronger than ever.

To get a firsthand sense of why 536 CE was hard going across much of the world, the Byzantine historian Procopius made a note of the time in his account of the Persian Wars:

"For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during this whole year, and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear nor such as it is accustomed to shed."

Today, it appears this sun-shielding fog had its origins in a series of volcanic eruptions across the Americas, which spewed enough ash into the atmosphere to turn summer into winter across much of the Northern Hemisphere.

Just five years later, a good chunk of the Roman population would fall beneath a plague like no other. Oh, and another colossal volcanic event, this time in El Salvador, churned out even more ash to top it all off.

Life in North America wasn't much better. Measurements of tree rings from northern Arizona reveal a drop in temperature and precipitation that lasted for decades.

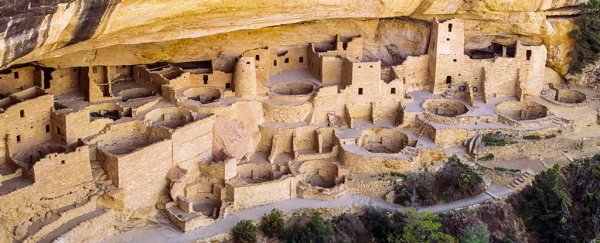

Yet archaeological records show that in spite of these challenging times, the Ancient Puebloans would go on to develop a rich, complex culture that would thrive for centuries.

To gain a clearer perspective on just how their founding agrarian communities coped with a harsh and sudden climate shift, the researchers amassed a database of hundreds of food materials and their radiocarbon dates, all collected from 230 dig sites across the region.

The ages, densities, and locations of the agricultural products reflected a story already familiar to archaeologists, of a widespread population – broken up into lots of smaller, localized settlements – practicing farming techniques that suited their local conditions.

Up to around 400 CE, the land was a patchwork of foragers and farmers. Some were more the latter, growing more substantial crops that included maize and beans to supplement diets.

Significantly, by the 6th century, a sharp rise in population growth began to limit the amount of farmland available. Where dispersed kin groups were once keen to pack up and move when opportunities presented, by the middle of the century they were sitting tight and collaborating with their neighbors in more complex social groups.

Comparing the evidence of this cultural mixing in their database with the climate records represented by tree rings from the Colorado Plateau, the researchers argued there was a strong link between the climate changes and cultural shifts.

"Archaeologists have long recognized that demographic and social change transformed Ancestral Pueblo societies during the late 6th and early 7th centuries CE, but we contend that these changes are best understood when juxtaposed with the consequences of extreme cold at the beginning of this interval," the team writes.

The hardships in the wake of the year 536 CE put the mix of emerging communities across the southwest to the test. Some could reorganize, developing socio-political ties that saw them through. Others failed to flourish. In the end, the years from hell served as a selection process for cultural practices that could bring people together and allow them to share their experience to weather the tough times.

For instance, an ancient farming community that occupied the Cedar Mesa and Grand Gulch was known to raise domesticated turkeys. By 550 CE, this practice was common across the entire southwest region, indicating a sharing of knowledge and a push to diversify food sources.

Within a few generations, the skies cleared once more and good times returned. Armed with new cooperative social practices, the Ancient Puebloans would go on to establish a rich, resilient civilization that would last centuries.

Of course it wasn't all rainbows and turkey dinners. With sedentary lifestyles and complex political systems come their own challenges and risks of inequality. But in the wake of numerous shake-ups, the Ancient Puebloans always seemed to find a way to come back strong, until finally vanishing in search of new lands in the 14th century.

Even today, traces of their farming practices can be found living on in cultures such as the Hopi.

Faced with our own years of hardship, we might take heed of the resilience the Ancient Puebloans found in coming together to share knowledge. And hope we too might emerge stronger in the years ahead.

This research was published in Antiquity.

Editor's note (8 Dec 2021): The original headline of this article referred to Ancient Puebloans as 'American', meaning their geographical, North American location. This has been clarified to avoid confusion with modern American culture.