In the area where the Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexican borders now meet, ancestral Pueblo societies thrived and then collapsed several times, over the span of 800 years.

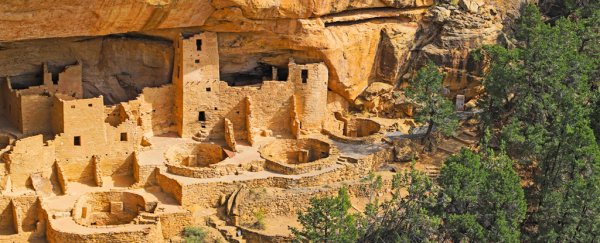

Each time they recovered, their culture transformed. This shifting history can be seen in their pottery and the incredible stone and earth dwellings they created. During 300 of those years, some Pueblo peoples, who also used ink tattoos, were ruled by a matrilineal dynasty.

As in the collapse of other ancient civilizations, ancestral Pueblo social collapses align with periods of changing climate - but Pueblo farmers often persevered through droughts, suggesting that there was more to their collapses than just environmental conditions.

So archaeologists took a closer look at what was happening in these societies, before 1400 CE, leading up to their times of upheaval. Using tree-ring analyses of wood beams for building construction allowed the researchers to construct a time series of the Pueblo societies' productivity.

Peak construction periods were clustered around good maize growing seasons, even though these times, on average, were not climatically better for growing maize than when there was a lull in said construction.

The new research found that while the societies often bounced back fairly quickly after construction lulled, there were distinct slow-downs in recovery that coincided with increased signs of violence.

This sort of system slowdown can be seen in other regional collapses of ancient societies like the Neolithic Europeans, that had no link to changing climates. It's also a feature of complex systems as diverse as the tropical rainforest and the human brain.

"Those warning signals turn out to be strikingly universal," said Wageningen University complexity scientist Marten Scheffer. "They are based on the fact that slowing down of recovery from small perturbations signals loss of resilience."

Scheffer and colleagues suspect slowly accumulating social tensions - like wealth inequality, racial injustice, and general unrest - wore away at social cohesion until all it took was a bit more pressure from another drought to tip them over the edge. This appears to have happened to the Pueblo peoples around 700, 900, and 1140 CE.

However, during the late 1200s, a combination of drought and external conflict spurred the ancestral Pueblo peoples to permanently leave the region.

"Societies that are cohesive can often find ways to overcome climate challenges," explained Washington State University archaeologist Tim Kohler.

"But societies that are riven by internal social dynamics of any sort – which could be wealth differences, racial disparities or other divisions – are fragile because of those factors. Then climate challenges can easily become very serious."

The ancient Pueblo peoples did find a way to thrive elsewhere, possibly by dramatically transforming their culture once more, and today their descendants live on tribal lands surrounding the empty places that were once the center of the Pueblo world. Their history provides us with a significant warning.

"Today we face multiple social problems including rising wealth inequality along with deep political and racial divisions, just as climate change is no longer theoretical," Kohler said. "If we're not ready to face the challenges of changing climate as a cohesive society, there will be real trouble."

If we want to avoid repeating history, we'd better pay attention.

Their research was published in PNAS (link not yet live at time of writing).