The fastest-shrinking glacier in Greenland has made an unexpected turn.

Although it's been melting for 20 years, the Jakobshavn Glacier in West Greenland - famous for producing the iceberg that sank the Titanic - has now started growing again.

Since the 1980s, waters have been growing warmer around Baffin Bay, where the glacier meets the sea. But, recent NASA data reveal that, in 2016, ocean current grew colder.

As a result, the ice of Jakobshavn Glacier has been thickening, flowing more slowly, and growing towards the ocean.

The waters around the mouth of the glacier - also known as Sermeq Kujalleq in Greenlandic - are now the coolest they have been since the 1980s.

"At first we didn't believe it," said glaciologist Ala Khazendar of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "We had pretty much assumed that Jakobshavn would just keep going on as it had over the last 20 years."

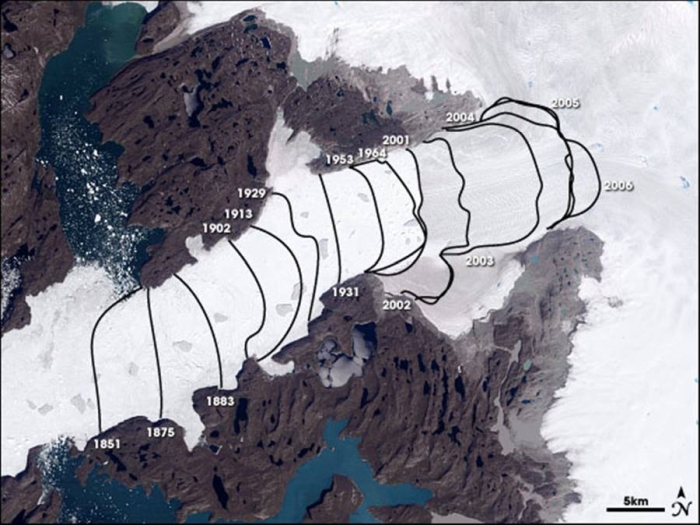

Jakobshavn's calving front from 1851 to 2006. (NASA Earth Observatory)

Jakobshavn's calving front from 1851 to 2006. (NASA Earth Observatory)

But over the last three years, that cold water has kept coming, according to data from NASA's Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) mission and other sources.

In a new paper, Khazendar and his team have identified the cause - and, yes, it is only temporary.

The team traced the current using observations and a NASA-developed ocean modelling system to fill in the gaps in the data.

The cooling began in the North Atlantic Ocean, 966 kilometres (600 miles) south of the glacier, triggered by a climate pattern called the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO): every five to 20 years, atmospheric pressure at sea level fluctuates, ultimately resulting in either warming or cooling, which is then carried northward by the ocean currents up the southwestern coast of Greenland.

In 2016, the water in this current was cooler by 1.5 degrees Celsius, cooling the Atlantic around Greenland by about 1 degree Celsius; this made its way to the mouth of Jakobshavn, allowing the ice to thicken.

Seems like such a tiny increment for such a big effect, doesn't it? Even the researchers were surprised.

"We didn't think the ocean could be that important," OMG principal investigator Josh Willis of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory told National Geographic.

But, inevitably, the pendulum will swing back, and the glacier will shrink again.

Meanwhile, the rest of Greenland's ice sheet is still receding; and, even if this slight growth were to continue, it couldn't possibly make up for the intense losses experienced so far.

Some of the oldest and thickest ice in the Arctic broke last year - the first time on record it has done so. And it happened twice.

Over half the Arctic's permanent ice has melted; and melting ice and snow has revealed Arctic landscapes hidden for 40,000 years.

In fact, according to a report by the UN last year, we are past the point of no return. The damage has been done; the Arctic is warming, and there's nothing we can do to stop it.

Jakobshavn has been melting since the early 2000s, when it lost its ice shelf. This floating platform of ice slows a glacier's flow; so, when Jakobshavn's broke off, its flow increased.

Since then, its melt has been accelerating, and the glacier's front retreating from the ocean. Between 2013 and 2016, it lost 152 metres (500 feet) of thickness.

Jakobshavn hasn't even come close to replacing that bulk, and it probably won't. The NAO cooling is unlikely to outpace warming.

"Jakobshavn is getting a temporary break from this climate pattern. But in the long run, the oceans are warming. And seeing the oceans have such a huge impact on the glaciers is bad news for Greenland's ice sheet," Willis said.

This research demonstrates that glacial recession is not a one-way trend, but it doesn't show a reversal of climate change. It does indicate that the effects are a little more complex than we thought, but, ultimately, that bird has flown the coop.

"This cooling is going to pass," Khazendar told National Geographic. "When it does, the glacier is going to retreat even faster than it was before."

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.