The weather was closing in. For a week, cryosphere scientist Luke Trusel and his team hadn't been able to access their remote drill site in western Greenland, and if they didn't act now, there was no telling when they'd get another chance.

Spying a brief window where helicopter flight was safe, the researchers grabbed only minimal gear and made for the camp, where they drilled an ice core – their deepest of the season – in a straight 24-hour stretch, breaking only briefly to sleep in a cramped, chilly tent.

It was worth it. The results of their polar all-nighter confirm that Greenland's massive ice sheet – the leading source of new water added to the ocean every year – is melting faster than at any point in recent centuries. And probably far beyond.

"Melting of the Greenland ice sheet has gone into overdrive," Trusel, from Rowan University in New Jersey, told ScienceAlert.

"It's now melting more than at any point in at least the last four centuries, and probably more than at any time in the last 7 to 8 millennia."

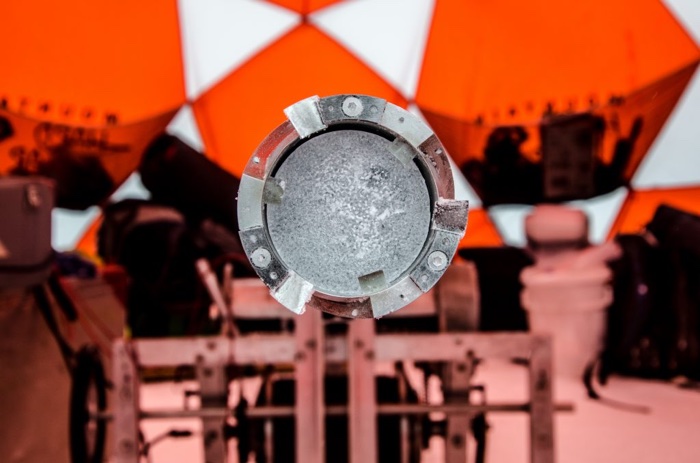

(Sarah Das/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

(Sarah Das/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Before now, scientists were well aware Greenland's ice sheet was in a perilous place, with studies showing serious problems with the country's ice caps and glaciers too.

But it's the ice sheet that's most concerning.

As the world's second largest body of ice, when it melts, it melts a lot. We're talking about a billion tonnes of ice vanishing every single day. You know where it goes.

In fact, if all of it were to disappear in a hot-enough world, we'd be looking at almost 7.5 metres (24 feet) of sea level rise.

Short of rapidly slashing carbon emissions – or wishfully geoengineering the planet somehow – our best proposals for holding off such a disastrous outcome do not seem particularly realistic.

But while the melt clearly proceeds at a scary pace, existing records have made it difficult to quantify just how scary the pace is in the context of recent world history.

Satellite observations of Greenland's ice melt only give us about 40 years of data to play with, and reliable modelling for the region doesn't extend back further than the 1960s.

(Sarah Das/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

(Sarah Das/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

"Before this 'observational era', there is much larger uncertainty with how the ice sheet has melted, especially how much of that melt water has left the ice sheet through runoff," Trusel says.

"Using our ice cores, we are effectively able to extend the satellite record 10fold."

Ice cores preserve lots of interesting things. Extracted from depths several hundred metres below the surface, these frozen columns of ancient water offer new insights into basically anything: pollution in the time of the Black Death, Earth's leaking oxygen supply, the history of the Roman Empire, even forces that conspire to slay gods.

In this case, Trusel's team used multiple cores to piece together a record of the last 364 years of melting ice in Greenland, giving us an unprecedented perspective on the epic ice sheet's fade to blue.

What they found is that increases in melting intensity began shortly after the onset of industrial-era Arctic warming in the mid-1800s, but it's during a much more recent timeframe that things got really wet.

Results from two of the cores "show a pronounced 250 percent to 575 percent increase in melt intensity over the last 20 years, relative to a pre-industrial baseline period," the authors write in their paper.

"Furthermore, the most recent decade contained in the cores (2004–2013) experienced a more sustained and greater magnitude of melt than any other 10-year period in the ice-core records."

(Sarah Das/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

(Sarah Das/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

In other words, the melting is increasing dramatically. But it's not just picking up speed in a straight line – the analysis shows the melting is accelerating in a non-linear curve.

"The chart of runoff looks like a hockey stick," Trusel says.

"Melting has not just increased, it's accelerating in response to a warming atmosphere. This means warming is more impactful today than it was even 50 years ago."

According to Trusel, the most concerning part of this anomalous acceleration is we haven't seen the worst yet. Far from it.

"This response has recently exceeded anything we've seen for the last four centuries, and it will continue to respond to today's warmth for decades, centuries, or millennia," he says.

"Because ice sheet melting in response to a warming atmosphere increases exponentially, this means the sea level rise we've seen already will pale in comparison to what might be expected in the future as climate continues to warm."

If there's a silver lining in these grim findings, it's that now we have an overview of the Greenland ice sheet's long-term melting behaviour, maybe – just maybe – we can do something about it.

The world's decision makers are right now meeting in Poland to help shape what may be our generation's last chance to decisively mitigate the worst repercussions of climate change.

If a billion tonnes of lost ice a day (and rising) isn't enough to get their attention, well, you can't blame nature for trying.

"To me, this is a wakeup call. A warning from the climate system," Trusel says.

"The question remains: do we heed the warning, and work to reduce emissions and limit warming and thus Greenland melt? Or do we ignore it? What happens next?"

The findings are reported in Nature.