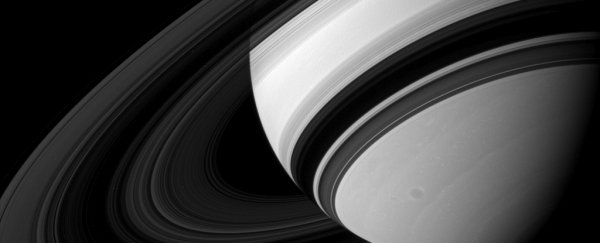

In the last weeks before it plunged into the stormy heart of Saturn a year ago, Cassini did something no other probe has done before. It swooped in between the planet and its signature rings, instrumentation furiously collecting data all way until the absolute end.

And in those final orbits, it was bathed in unexpectedly heavy rain from Saturn's innermost D ring, which, as it turns out, hurls dust grains coated in a chemical cocktail from the rings that is "surprising" in its complexity, researchers have said.

And over time, that material could alter the carbon and oxygen content in Saturn's atmosphere.

"This is a new element of how our Solar System works," said astronomer and physicist Thomas Cravens of the University of Kansas.

"Two things surprised me. One is the chemical complexity of what was coming off the rings - we thought it would be almost entirely water based on what we saw in the past. The second thing is the sheer quantity of it - a lot more than we originally expected. The quality and quantity of the materials the rings are putting into the atmosphere surprised me."

Based on previous research, some ring rain was expected, so Cassini was prepared - the probe used its radio antenna like an umbrella to protect itself from the falling debris.

The probe could then use its Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) to analyse the chemical content of this rain, even though it was designed to analyse gases.

The ring rain hit Cassini at such tremendous velocity that it instantly vaporised - which meant INMS could get to work.

"Molecular hydrogen was, as expected, the most abundant atmospheric constituent," said cosmochemist Kelly Miller of the Southwest Research Institute.

"But the downpour coming from the rings included plenty of water as well as molecules like butane and propane - the kind of chemicals you might use for a grill or camping stove."

The researchers also found methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, molecular nitrogen and carbon dioxide.

The methane, Cravens said, was wholly unexpected, as was the carbon dioxide. What the researchers were expecting was a lot more water ice.

Not only were there organic compounds mixed up in the ice; the composition of those molecules was different from the organic compounds observed on Enceladus and Titan.

A second study looked at 2,700 grains of dust captured from the ring rain in Cassini's Cosmic Dust Analyzer instrument, and found that, while most of the material (around 95 percent) was water ice, there was also a not insignificant proportion of silicates - the molecules that make up rocks.

And the researchers found that the D ring, spinning much faster than the planet's atmosphere, is hurling this material into the planet, as much as 10,000 kilograms (22,000 pounds) per second.

This suggests that the next ring, the C ring, is somehow replenishing the D ring - and that the D ring is playing a role in the composition of the planet's ionosphere and atmosphere.

These findings could help us understand more about planetary rings, what they're made of, where they come from, how long they last and why some planets get them and some don't.

They also shed some light on the lifespan of rings, which, after all, don't actually last forever, as seen on the thin, wispy rings around Jupiter, Neptune and Uranus.

"Because of this data, we now have shortened the lifetime of inner rings because of the quantity of material being moved out - it's much more than we thought before," Cravens said.

"If it's not being replenished, the rings aren't going to last - you've got a hole in your bucket. Jupiter probably had a ring that evolved into the current wispy ring, and it could be for similar reasons."

Other discoveries made during those 22 ring dives include a previously unknown radiation belt between Saturn and its rings, and an electric current that runs along magnetic field lines between the D ring and Saturn's atmosphere.

The team's research (and several other findings from those dives) have been published in the journal Science.