New research has revealed that a gene variant known to be a major risk factor for Alzheimer's disease can predict the decline of mental capacities separately from the protein tangles involved in the disease.

The gene variant, called APOE4, is linked to damaging the blood-brain barrier that normally helps to keep toxins out of the brain. According to the new results, it looks like having this APOE4-related damage predicts cognitive decline independently of the build-up of amyloid beta or tau protein plaques, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

The smallest blood vessels in the brain, which help to keep it sealed and protected, are put under threat by APOE4. This latest study shows that once these perimeters are breached, memory and cognitive function can start to suffer.

As with any new discovery related to Alzheimer's - a field of research that sees constant developments - the hope is that a better understanding of the disease could lead to better ways to treat it; at the moment, there's no known cure.

"This study sheds light on a new way of looking at this disease and possibly on treatment in people with the APOE4 gene, looking at blood vessels and improving their function to potentially slow down or arrest cognitive decline," says neuroscientist Berislav Zlokovic, from the University of Southern California (USC).

"Severe damage to vascular cells called pericytes was linked to more severe cognitive problems in APOE4 carriers. APOE4 seems to speed up the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier by activating an inflammatory pathway in blood vessels, which is associated with pericyte injury."

APOE4 is one of the variants of apolipoprotein E, responsible for encoding a protein that carries cholesterol around the brain. Having one or two copies of APOE4 is known to increase the risk of someone developing late-onset Alzheimer's, although it's not a guarantee the person will get it.

Researchers have been working hard to figure out why APOE4 is a major risk gene for Alzheimer's; we do know the gene variant has been strongly linked to damage to the blood-brain barrier before, in both human tissue and animal tests.

The integrity of the blood-brain barrier, and the health of the pericyte cells that play a key role in that barrier, are important in shielding the brain from damage. There's a correlation between disruption of the barrier and cognitive decline, as seen in people with Alzheimer's disease, but scientists haven't been sure about there being a causal link, too.

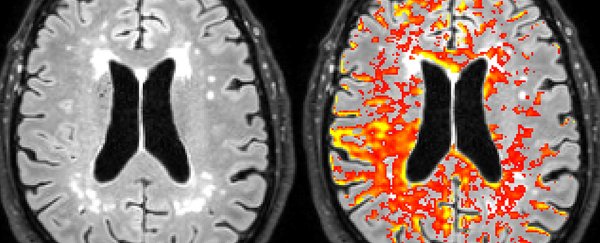

In the new study, researchers used memory tests, neuroimaging, and biomarkers across 435 study participants – some with healthy cognition and some with mild cognitive impairment associated with the early stages of Alzheimer's disease.

APOE4 carriers in both these groups showed signs of a leaky blood-brain barrier in specific areas that are important for memory and cognition – the hippocampus and the parahippocampal gyrus – though the leakage was worst in APOE4 carriers whose cognitive decline had already begun.

Further tests showed tissue loss in the hippocampus and the parahippocampal gyrus had not yet started, suggesting blood-brain barrier leaks occur sometime before the brain starts to suffer. The scientists also found signs of higher pericyte injury, and more activity on the inflammatory pathways leading to pericyte injury, in the APOE4 carriers.

The fact that blood-brain barrier leaks could predict cognitive decline independently of the amyloid beta and tau protein levels in the patients' brain could be a major clue.

"These observations cast new light on APOE4 that runs contrary to the widely held idea that this gene variant contributes to Alzheimer's disease solely by promoting amyloid beta and tau accumulation," write neuroscientists Makoto Ishii and Costantino Iadecola in an accompanying News & Views article in Nature.

"Instead, it seems that blood-brain barrier dysfunction might explain why APOE4 carriers are susceptible to Alzheimer's disease."

It may be that finding a reliable treatment for Alzheimer's disease relies on attacking it on multiple fronts – but in the meantime, the more we know about what causes it, and the earlier we can detect it, the better.

The research has been published in Nature.