It's been clear for a while now that there's too much carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere, heavily contributing to a warming planet, and now scientists have come up with a new plan for dealing with all this excess CO2 – converting it into plastic.

Plastic itself isn't the most environmentally friendly of materials, but not only would it mean that CO2 gets converted into something useful, it could also reduce the need to produce plastics out of fossil fuels, giving us a better chance of hitting targets for limiting climate change.

The new approach is the most efficient method yet that scientists have devised for converting carbon dioxide into ethylene, the raw material used to make the most commonly used plastic, polyethylene.

And it brings the possibility of a practical CO2-to-plastic conversion system a whole lot closer.

"I think the future will be filled with technologies that make value out of waste," says lead researcher Phil De Luna, from the University of Toronto in Canada.

"It's exciting because we are working towards developing new and sustainable ways to meet the energy demands of the future."

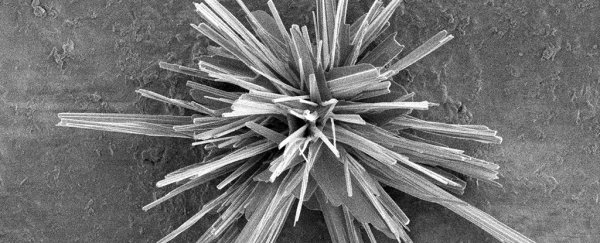

The team used a technique involving X-ray spectroscopy and computer modelling techniques at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) facility at the University of Saskatchewan – analysing matter with electromagnetic radiation to identify their key catalyst.

And it was thanks to a new piece of equipment developed by CLS senior scientist Tom Regier that the researchers were able to study both the shape and the chemical environment of the catalyst in real time.

"This has never been done before," says one of the team, Rafael Quintero-Bermudez, also from the University of Toronto. "This unique measurement allowed us to explore a lot of research questions about how the process takes place and how it can be engineered to improve."

"This experiment could not have been performed anywhere else in the world, and we are thrilled with the results," adds De Luna.

The catalyst is necessary to power a carbon dioxide reduction reaction, converting CO2 into other chemicals when it gets hit with an electrical current. While many metals can act as catalysts, we already know that copper is the only one that can produce ethylene.

The researchers worked out how to control the reaction so that ethylene production was maximised, while waste products such as methane were kept to a minimum.

"Copper is a bit of a magic metal," says De Luna. "It's magic because it can make many different chemicals, like methane, ethylene, and ethanol, but controlling what it makes is difficult."

Armed with this new knowledge and a suitable carbon capture technology, we could potentially remove CO2 from the atmosphere while producing plastics in an environmentally friendly way at the same time.

As long as the energy required for the conversion can be provided by a renewable source, and the resulting plastics can be reused or recycled later in life, the overall impact should be a positive one.

With polyethylene production now over 100 million tonnes a year, we're talking about a big difference to our planet's atmosphere. Further research is required to refine the technique, but we now have one of the basic building blocks.

And what makes the story even more special is that the scientists came close to giving up.

"We were about to give up, but when the results came in, they were so good we had to sit down," says Quintero-Bermudez. "Really beautiful results."

The findings have been published in Nature Catalysts.