Diamonds are hardly ever perfect. Like us, they carry blemishes and flaws: tiny 'inclusions' of ancient chemistry trapped inside their lustrous frames.

To the jeweller, these minuscule marks may diminish a gemstone's value. To a scientist, the imperfection itself can actually be the true glittering prize.

In a startling new discovery, researchers in Canada have found something the world has never seen before: a previously unknown mineral with a very unusual chemical signature, hidden inside a diamond from South Africa.

For such a giant discovery, it's a wonder they found anything at all.

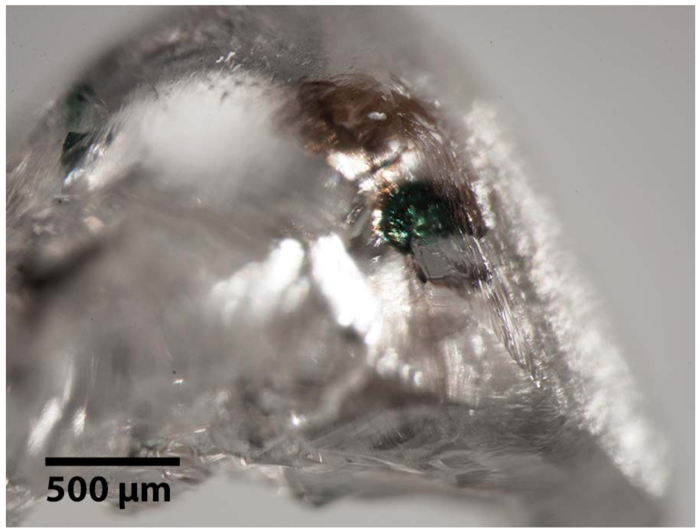

Only a single grain of this strange new mineral – called goldschmidtite – was found, with the whole mass inside the diamond measuring just 100 micrometres (approximately the width of a human hair).

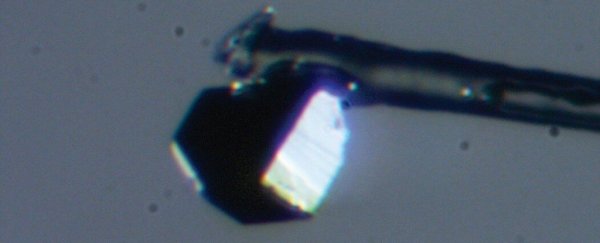

The diamond encasing the goldschmidtite grain, before breakage. (Meyer et al., American Mineralogist, 2019)

The diamond encasing the goldschmidtite grain, before breakage. (Meyer et al., American Mineralogist, 2019)

Despite its modest size, the material contained inside this speck is wholly new to science. It offers a unique record of chemistry from a long time ago, inside the deep, ancient parts of the planet, the researchers say.

"Goldschmidtite has high concentrations of niobium, potassium, and the rare earth elements lanthanum and cerium, whereas the rest of the mantle is dominated by other elements, such as magnesium and iron," explains University of Alberta PhD student Nicole Meyer.

"For potassium and niobium to constitute a major proportion of this mineral, it must have formed under exceptional processes that concentrated these unusual elements."

The tiny sample, which is dark-green in colour, is estimated to have formed at a depth of about 170 kilometres (105 miles) below the surface, based on geothermobarometric analysis.

The mineral, formulaically known as (K,REE,Sr)(Nb,Cr)O3, is chemically similar to an engineered perovskite-structured crystal called potassium niobate (KNbO3), but is only the fifth known naturally occurring perovskite-group mineral ever seen in Earth's mantle.

The goldschmidtite sample – named in honour of the Norwegian geochemist Victor Moritz Goldschmidt (1888–1947) who helped to pioneer perovskite mineralogy – was retrieved from the Koffiefontein kimberlite pipe in South Africa's Kaapvaal Craton.

Kaapvaal Craton is home to some of the oldest rocks on the planet, giving scientists fertile territory for all sorts of mineral discoveries, some of which occur in diamonds.

And why not? If you're going to travel from very far underground into the very distant future, diamond makes for a decent time capsule, all things considered.

"As a chemically inert and rigid host, diamond can preserve included minerals for billions of years," the paper explains, "and thus provide a snapshot of ancient chemical conditions in cratonic keels or deep-mantle regions."

The findings are reported in American Mineralogist.