Strange things are afoot in the Milky Way.

According to a new analysis of Gaia satellite data, the closest star cluster to our Solar System is currently being torn apart - disrupted not just by normal processes, but also by the gravitational pull of something massive we can't see.

This disruption, astronomers say, could be a hint that an invisible clump of dark matter is nearby, wreaking gravitational havoc on anything within its reach.

Actually, star clusters being pulled apart by gravitational forces is inevitable. A star cluster is, as the name suggests, a tight, dense concentration of stars. Even internally, the gravitational interactions can get pretty rowdy.

Between those internal interactions and external galactic tidal forces - the gravity exerted by the galaxy itself - star clusters can end up pulled apart into rivers of stars: what is known as a tidal stream.

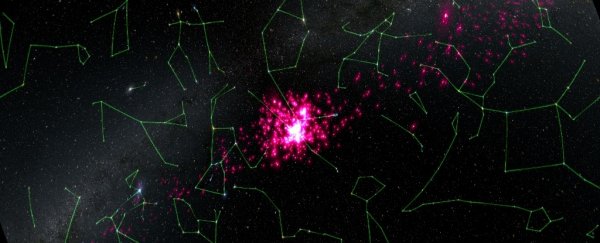

These streams are hard to see in the sky, because it's often quite tricky to gauge stellar distances, and therefore group stars together. But the Gaia satellite has been working to map the Milky Way galaxy in three dimensions with the most detail and highest precision achievable, and the most accurate position and velocity data on as many stars as possible.

Because stars pulled from a star cluster still share the same velocity (more or less) as the stars in the cluster, the Gaia data has helped astronomers identify many previously unknown tidal streams, and star clusters with tidal tails - threads of stars that have started to come loose from the cluster both in front and behind it.

In 2019, astronomers revealed they had found evidence in the second Gaia data release of tidal tails streaming from the Hyades; at 153 light-years away, it's the closest star cluster to Earth.

This caught the attention of astronomer Tereza Jerabkova and her colleagues from the European Space Agency and the European Southern Observatory. When Gaia Data Release 2.5 (DR2.5) and DR3 became available, they homed in, expanding the search parameters to catch the stars the earlier detections had missed.

They found hundreds and hundreds of stars associated with the Hyades. The central cluster is about 60 light-years across; the tidal tails span thousands of light-years.

Having such tails is fairly normal for a star cluster disrupted by galactic tidal forces, but the team noticed something weird. They ran simulations of the cluster's disruption, and found significantly more stars in the trailing tail of the simulation. In the real cluster, some stars are missing.

The team ran more simulations to find out what could cause these stars to go astray - and found that an interaction with something big, about 10 million times the mass of the Sun, could reproduce the observed phenomenon.

"There must have been a close interaction with this really massive clump, and the Hyades just got smashed," Jerabkova said.

The big problem with that scenario is that we can't currently see anything that massive anywhere nearby. However, the Universe is actually full of invisible stuff - dark matter, the name we give to the mysterious mass whose existence we can only infer by its gravitational effects on the things we can see.

According to these gravitational effects, scientists have calculated that roughly 80 percent of all matter in the Universe is dark matter. It's thought that dark matter is an essential part of galaxy formation - large clumps of it in the early Universe collected and shaped the normal matter into the galaxies we see today.

Schematic diagram of our galaxy's dark matter halo. (Digital Universe/American Museum of Natural History)

Schematic diagram of our galaxy's dark matter halo. (Digital Universe/American Museum of Natural History)

Those dark matter clumps can still be found today in extended 'dark halos' around galaxies. The Milky Way has one thought to be 1.9 million light-years across. Within those halos, astronomers predict denser clumps, called dark matter subhalos, just drifting around.

Future searches may turn up a structure that could have caused the weird disappearance of stars in the trailing tail of Hyades; if they don't, the researchers think the disruption could be the work of a dark matter subhalo.

The finding also suggests that tidal streams and tidal tails could be excellent places to look for sources of mysterious gravitational interactions.

"With Gaia, the way we see the Milky Way has completely changed," Jerabkova said. "And with these discoveries, we will be able to map the Milky Way's sub-structures much better than ever before."

The research has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.