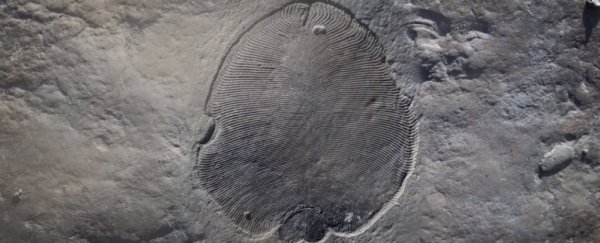

We don't know a lot about the world's earliest animals, but thanks to their 558 million-year-old fossilised remains, we thought we had a hint as to their appearance.

Now, it seems, we were wrong about even that. Scientists at the Australian National University (ANU) have discovered that the iconic Dickinsonia fossils are probably not flat sea creatures with ribbed bodies.

As it turns out, the iconic image of their fossilised imprints may simply be their "skeleton". Or, since these organisms didn't technically have skeletons, an outline of their more resilient tissue.

"Now we know that what we are looking at is an impression of a soft organic skeleton that may have been anywhere within Dickinsonia's body," says lead author Ilya Bobrovskiy, a biogeochemist from the Australian National University.

"What we're seeing could be a part of Dickinsonia's bottom, the inside of its body or part of its back."

The discovery opens up even more possibilities - too many, in fact - on what these ancient sea creatures might have looked like.

"These soft-bodied creatures that lived 558 million years ago on the seafloor could, in principle, have had mouths and guts - organs that many palaeontologists argue emerged during the Cambrian period tens of millions of years later," explains Bobrovskiy.

The Dickinsonia genus is part of a curious group of lifeforms known as the Ediacaran biota. In the seventy years since these were first discovered, scientists have been coming up with various hypotheses on what these fossils actually are: whether we're dealing with algae, protozoans, lichens, colonies of bacteria, jellyfish, coral, worms, or a type of mushroom.

Bobrovskiy and his team were the first to look beyond their mere appearance. Analysing molecules within these remains last year, the team stumbled upon cholesterol - fat molecules that are considered hallmarks of animal life and even more evidence that Dickinsonia are indeed the earliest animal ancestors.

Now, their new research could potentially top that. Analysing the physical properties of the limestone sediment, Bobrovskiy and his team have figured out for the first time how these fossils stayed so well-preserved for billions of years.

It's a mystery that's been plaguing researchers since the fossils were first discovered. But even though Dickinsonia don't have hard skeletons or shells, it turns out they do have different types of tissue, some of which are tougher to degrade.

To get an idea of how the imprint came to be, the team turned to melting ice. Using ice from a mould shaped like the Death Star, the researchers mimicked what would happen to a slowly degrading organism that consisted of different types of tissue.

The top of the ice Death Star was made out of stronger, more durable ice; a corrugated cardboard sheet was placed in the middle to represent the most resilient tissue.

"As the ice cast melted, it was replaced by sediment from below, creating a negative-hyporelief impression," the authors write.

"The cardboard sheet was pushed up to the top of the cast, forming an impression of its corrugations in the overlying sand."

In other words, as the model began to decay, the softer sediment around it gradually filled in the gaps, creating a cast of the cardboard leftover.

The idea that Dickinsonia had multiple types of tissue, some of which degrade slower than others, suggests that these creatures were far more complex than we thought, adding even more evidence to the idea that they are the world's earliest known animal.

"Imagine you've never seen a human being, you've never seen a dinosaur or a bird," Bobrovskiy told The Sydney Morning Herald.

"The same way we have never seen other organisms that look like the Ediacaran creatures [means we] have as much difficulty as aliens would have had with reconstructing dinosaurs."

It just goes to prove, you should never judge an organism by its fossil.

This study has been published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.