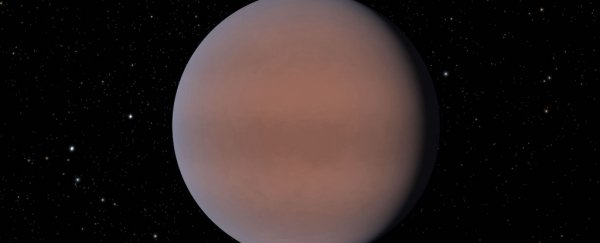

New Year's Day comes around once every 47.5 hours on the roughly Neptune-sized exoplanet TOI 674b, which makes it something of a rare creature.

In spite of years of hunting, surprisingly few middle-sized gas giants have ever been seen with orbits shorter than a few days in length, creating what astronomers refer to as a Neptunian desert of incredibly hot, star-skimming planets of intermediate masses.

Exactly why this is the case is a bit of a mystery. After all, a number of super-Earth sized balls of rock (like the toasty hot TOI 270b) are seen whipping around their star quick time. Hot Jupiters with orbits measurable in hours also pop up regularly.

So where are all the hot Neptunes? Something about their size, composition, or their positioning in their solar system makes them far less likely to be finding themselves getting too personal with a nearby star. Or on the rare occasion they do, they don't stick around long enough to brag about it.

Fortunately, astronomers have now noticed something else unusual about this recently discovered middle-range giant, a finding that could help tell us why it's so special: there happen to be hints of water floating in its atmosphere.

Observing the signature of water on planets far from our own oceanic world is exciting for a number of reasons, not least in telling us just how unique our own planet might be.

But having a breakdown of the kinds of gases in an exoplanet's atmosphere – particularly water vapor – is like having the details of its cosmic birth certificate, giving planetary scientists a clearer understanding of how and where it formed in its solar system.

Planets that form beyond a point where the star's radiation can easily sublimate ice into gas will have a much better chance of holding onto water, for example, raising the chances that a short-orbit Neptune with plenty of water is far from its place of birth.

The next step will be to collect more data on the precise amount of water in TOI 674b's atmosphere, as well as other features, such as its metallicity.

The planet has only been on our radar for around a year, following its discovery using data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. But it's already proved interesting enough for researchers to turn other instruments, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, towards the planet to probe its secrets. (The team also looked at older data from the retired Spitzer Space Telescope.)

At around half the mass of our own Sun, the M-class red dwarf star it orbits isn't particularly bright, meaning there's enough light to see by, but not so much the planet gets lost in the glare. Better still, at a distance of just 150 light years away, the whole planetary system is more or less in our backyard.

This trifecta of closeness to the parent star, proximity to us, and gentle wash of radiation means current generation spectrographs can have a much easier time analyzing the light glinting through its clouds.

One tool perfectly suited to studying exoplanets like it is the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope, with a design that will give us an unprecedented view of distant stars and their planets.

Knowing how TOI 674b fell into such a hot embrace with its star will help us fill in the bigger picture of how other solar systems evolve, and whether our own is boringly normal or a unique gem in an ocean of chaos.

The preprint is available on arXiv, and has been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal.