Just as the new year began, so too did an incredible new era of space exploration, with NASA confirming a successful flyby of the most distant world human beings have ever encountered.

(NASA)

(NASA)

As revellers watched fireworks exploding in the night sky, billions of kilometres beyond the spectacle, NASA's New Horizons probe quietly notched up another amazing first – making its closest approach to the most distant object ever visited by a spacecraft.

🚨First image of #UltimaThule! 🚨At left is a composite of two images taken by @NASANewHorizons, which provides the best indication of Ultima Thule's size and shape so far (artist’s impression on right). More photos to come on Jan 2nd! https://t.co/m9ys0VhmLA pic.twitter.com/qZu0KL8uJB

— Johns Hopkins APL (@JHUAPL) January 1, 2019

That object – nicknamed Ultima Thule – was first glimpsed at long distance by the Hubble Space Telescope back in 2014, but it wasn't until just now in 2019 that scientists got an up-close look to better understand this mysterious far-flung mass.

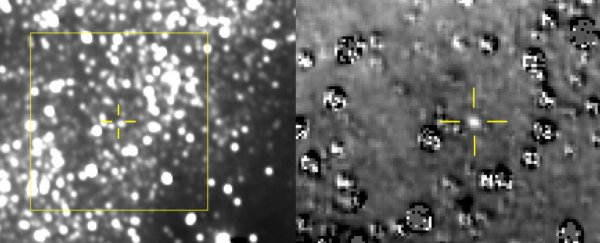

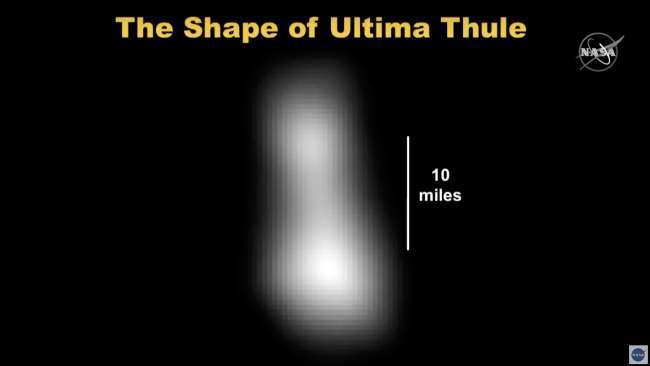

Thanks to the flyby, which brought New Horizons within about 3,500 kilometres (approx. 2,200 miles) of Ultima Thule at 12:33 am EST (05:33 UTC) Tuesday, we now know that this ancient, spinning object is shaped somewhat like a bowling pin, with approximate dimensions of about 32 by 16 kilometres (20 by 10 miles).

While the encounter might have taken place just after midnight on NYE, it wasn't until about six hours later that scientists at NASA, the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and the Southwest Research Institute actually received the first images of the flyby, thanks to the incredible distance the data had to be transmitted across space.

That's because Ultima Thule is located about 4 billion miles (6.4 billion kilometres) from Earth, in a still-little-understood region of space called the Kuiper Belt, made up of thousands of ancient trans-Neptunian objects orbiting the Sun – icy, rocky remnants from way back when the Solar System was young.

The most famous of these tiny outlier worlds – the dwarf planet, Pluto – was visited by New Horizons in 2015, and the Ultima Thule flyby represents the first major achievement of the probe's 'extended mission' after that – a milestone made all the more remarkable when you consider Ultima Thule hadn't even been discovered when New Horizons launched back in 2006.

(NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

(NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

Since then, over a decade's worth of scientific advancements has helped us to learn more about the Kuiper Belt and the strange worlds that might inhabit it, but there's no denying that this first up-close brush with an actual Kuiper Belt Object is an unprecedented accomplishment.

"New Horizons performed as planned today, conducting the farthest exploration of any world in history – 4 billion miles from the Sun," says principal investigator Alan Stern from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

"The data we have look fantastic and we're already learning about Ultima from up close. From here out the data will just get better and better!"

That better data won't take long to start turning up. While these early images represent our first up-close glimpse of Ultima Thule, scientists say we can expect to receive even sharper, higher-resolution pictures from tomorrow onwards – the first prizes of a 20-month haul of data New Horizons will transmit home.

That new data should help clear up some outstanding questions scientists still have about this distant object – including whether that bowling pin shape actually masks two closely co-orbiting objects (not one integrated mass), and how long it takes the spinning object to complete a rotation.

Watch this space – more answers are coming soon.