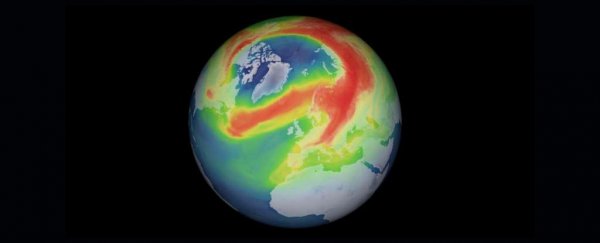

The unusually large hole that opened up in the ozone layer over the Arctic last year seems to have been triggered by record-breaking winter temperatures in the North Pacific ocean, according to new analysis.

The huge hole, which encompassed nearly the entire ozone layer overhead, closed in early spring, but there's a chance it could form a lot more frequently in the future.

Plugging satellite data into a series of simulations, researchers have found high sea surface temperatures in the North Pacific have the power to lower the temperature of the Arctic's westerly winds.

These high winds blow through winter into spring, and according to atmospheric models, if they grow cold enough for long enough, they can trigger the formation of polar clouds. At the North and South Pole, clouds in the stratosphere are a key ingredient in the severe ozone depletion process.

"The formation of the record Arctic ozone loss in spring 2020 indicates that present-day ozone depleting substances are still sufficient to cause severe springtime ozone depletion in the Arctic stratosphere," says ocean and atmospheric scientist Yongyun Hu from Peking University in China.

"These results suggest that severe ozone loss is likely to occur in the near future as long as North Pacific warm sea surface temperature anomalies or other dynamical processes are sufficiently strong."

Many of us are aware that a massive hole forms in the ozone layer above Antarctica every spring, but Arctic ozone is usually more resilient.

The planetary waves that flow between the ocean and the atmosphere in the Northern Hemisphere are much stronger than in the Southern Hemisphere. This means its winter winds are generally too warm for polar clouds to form in the stratosphere.

But when the surface of the Northern Pacific grows warmer than normal, past studies have found some planetary waves can grow weaker, reducing the temperature of the stratospheric vortex.

This is what seems to have happened in the spring of 2020. As a hole began to form in the Arctic ozone layer that spring, researchers noticed an associated weakening of a planetary wave labelled "wavenumber-1".

Plugging the data into a long-range model of the Arctic atmosphere, it appears a reduction in the strength of wavenumber-1 is probably the major factor that led to the unusually cold winds that blew over the Arctic between February and April 2020.

Without this wave weakening, a hole would likely have never formed.

"The formation of the record Arctic ozone loss in spring 2020 indicates that present-day ozone depleting substances are still sufficient to cause severe springtime ozone depletion in the Arctic stratosphere," explains Hu.

"These results suggest that severe ozone loss is likely to occur in the near future as long as North Pacific warm sea surface temperature anomalies or other dynamical processes are sufficiently strong."

The results could also help to explain mysterious losses of ozone in the past. In the spring of 2011, for instance, another large hole opened up in the Arctic ozone layer for no apparent reason. While it's still not clear why this happened, the authors think warm sea surface temperatures in the North Pacific could have been to blame, too.

At this time, we can't firmly say whether these particular spikes in ocean temperatures were due to natural variability or the result of human-caused global warming, but as our planet's oceans do absorb more and more heat with climate change, it's entirely possible the Arctic ozone layer is destined for more holes.

The study was published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.