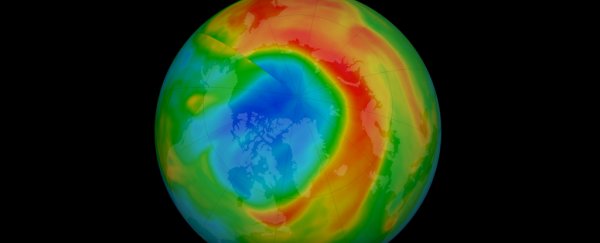

Earlier this year, the layer of ozone over the Arctic thinned out enough to be considered a serious sized hole. It wasn't exactly impressive compared with its southern cousin, but it was certainly a lot bigger than we'd ever seen it before.

Now, according to surveillance by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), we can breathe a sigh of relief. It's healed up again.

The unprecedented 2020 northern hemisphere #OzoneHole has come to an end. The #PolarVortex split, allowing #ozone-rich air into the Arctic, closely matching last week's forecast from the #CopernicusAtmosphere Monitoring Service.

— Copernicus ECMWF (@CopernicusECMWF) April 23, 2020

More on the NH Ozone hole➡️https://t.co/Nf6AfjaYRi pic.twitter.com/qVPu70ycn4

That's great news for ecosystems below, which rely on concentrations of ozone gas high up in the stratosphere to act as a planetary-scale sunscreen against damaging showers of UV radiation.

It wasn't the first time the ozone has thinned so dramatically above the Arctic, with a similarly concerning loss taking place back in 2011.

This year's event stands out as a real record breaker though. Most of the ozone around 18 kilometres (11 miles) overhead had vanished completely, raising concerns over whether changes to our planet's climate could give rise to even bigger, longer lasting holes in the future.

When we hear the words 'ozone hole', it's hard not to also think of ozone-busting pollutants like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Given the right conditions, these destructive molecules just love to get stuck into ozone's oxygens and split them apart.

Antarctica just so happens to have those 'right conditions' for half of the year. Strong polar winds concentrate the pollutants throughout the winter, while summer brings the necessary light energy and stratospheric cloud particles to get the reaction running.

The frozen cap on the other end of the planet isn't quite so unlucky. A whole lot of mountains and nearby land masses interfere with the Arctic's own vortex of winds, making a mess of its own ozone-destroying conditions and sparing the north of any significant damage.

At least, that's the usual story. This year's Arctic polar vortex was exceptionally strong, locking out a fresh supply of ozone from the tropics while driving temperatures down enough to generate stratospheric cloud particles for the chemical reaction to cling to.

With the polar vortex easing off, ozone can now drift back in without being quickly torn apart, closing up the hole for at least another year.

"CAMS will continue to monitor the evolution of the Arctic ozone hole over the coming months," the monitoring service reassures us.

It's taken years of international efforts to reduce CFC emissions enough to allow Antarctica's ozone to slowly regenerate, a feat that is still decades away from completion.

While fewer pollutants is also good news for the Arctic, it's hard to predict just how rising temperatures will affect its air currents in the future, with deviations in the polar vortex potentially becoming more frequent over time.

Prior to 2011's northern hole, nothing like it had been seen in over three decades of satellite records, raising the question of whether this year's record depletion will be topped any time soon.

We'll be sure to let you know if it comes back.