The Milky Way should be absolutely riddled with moons, when you think about it. The Solar System has 8 official planets, yet at least 25 times as many moons.

However, while we've confirmed nearly 5,000 exoplanets (that's planets outside the Solar System) to date, exomoons are scant, to say the least. One tentative detection was made in 2017; now, we finally have a second candidate to add to the mix.

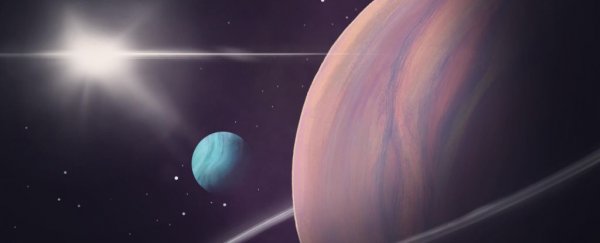

The exomoon candidate has been named Kepler-1708 b-i, orbiting an exoplanet orbiting a star some 5,500 light-years away. Evidence so far suggests that it's quite large – around 2.6 times the size of Earth, probably gaseous like a baby Neptune. Its host planet is just a little smaller than Jupiter.

This is similar to the first exomoon candidate, Kepler-1625 b-i, which is located some 8,000 light-years away, about the size and mass of Neptune (also likely gaseous), and orbiting an exoplanet up to several times the mass of Jupiter. Both exomoon candidates and their exoplanets are also orbiting their respective stars at quite large distances.

Both are very different from the moons we have here at home in the Solar System; but that only stands to reason.

"Astronomers have found more than 10,000 exoplanet candidates so far, but exomoons are far more challenging," said astronomer David Kipping of Columbia University, who also led the discovery of Kepler-1625 b-i with his colleague Alex Teachey of Columbia.

"The first detections in any survey will generally be the weirdo. The big ones that are simply easiest to detect with our limited sensitivity."

The exomoon candidate was revealed in a search of data collected by the Kepler space telescope (now retired; rest in space). Kepler's mission was to search for exoplanets. This is tricky, since exoplanets are too small and too dim to see directly most of the time; we have to look for them by trying to see the very small effects they have on their host stars.

In Kepler's case, this involved staring at stars, looking for very faint, regular dips in brightness that indicate something is moving between us and the star at regular intervals – in other words, an orbiting exoplanet. These very faint dips are known as a transit light curve.

In the data from Kepler, and later from Hubble, Kipping and Teachey identified a faint signal in addition to the exoplanet transit curve for Kepler-1625 b-i. Then they went back to the data looking for more such signals.

They studied the Kepler data for 70 exoplanets. Only an exoplanet called Kepler-1625 b was a match for an exomoon signal; but, the researchers said, a very strong one.

"It's a stubborn signal," Kipping said. "We threw the kitchen sink at this thing but it just won't go away."

Kepler-1708 b-i is yet to be confirmed, as is its predecessor; in fact, some astronomers have disputed whether Kepler-1625 b-i is an exomoon signature at all, instead suggesting that the signal was an artefact of data reduction.

Pre-empting such critique again, this time the researchers have calculated the possibility that the Kepler-1708 b-i signal is an artifact; it is, they said, just 1 percent.

Nevertheless, questions remain. We're not sure how a gas giant exoplanet and a gas exomoon system can form; since there's nothing like them in the Solar System, that suggests the formation mechanism is different from ones that formed the moons here. Perhaps the moons accumulated gas from their host exoplanets; or perhaps they started as exoplanets in their own right, and were captured in the gravitational fields of larger exoplanets.

Figuring it out will require more work; as will confirming whether or not the detection is indeed an exomoon. At the very least, follow-up observations will be needed to see if another instrument can also detect the signal. But it's entirely possible that the only way we will confirm the detection of exomoons is by… just continuing to find so many, that their existence can no longer be disputed.

Then, of course, the next challenge will be to find that rare and elusive beast, the moonmoon. For now, however, the chase for exomoons continues.

The team's research has been published in Nature Astronomy.