The more that scientists look into obesity, the more they realise its implications appear to reach far beyond the well-known effects on physiological health.

The brain also looks to be significantly affected in obese people, although the science on cause and effect remains far from clear. What isn't disputed is that brain 'shrink' and obesity has a worrying link, and new findings only serve to cement that association.

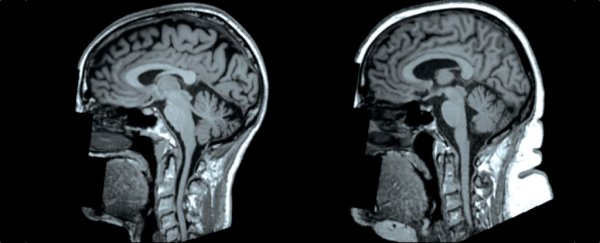

An MRI analysis of over 12,000 adults who took part in the UK Biobank study shows higher levels of body fat are linked to changes in the brain's form and structure, including having a reduced amount of grey matter – the neuron-rich mass responsible for processing much of our cognitive activity.

"We found that having higher levels of fat distributed over the body is associated with smaller volumes of important structures of the brain, including grey matter structures that are located in the centre of the brain," says radiologist Ilona A. Dekkers from Leiden University Medical Centre in the Netherlands.

These findings are similar to results published in January by a different team of researchers who also sourced data from the BioBank cohort, and found carrying extra belly fat was linked to a worrying amount of 'brain shrink' among the participants.

In the new study, which looked at people aged 45–76 years old (with an average age of 62), the researchers found the nature of the associations was different for men and women.

In men, a higher total body fat percentage was linked with lower grey matter volume overall, including the structures of the thalamus and hippocampus, but excluding the amygdala.

In women, higher body fat was only associated with reduced volume in one part of the grey matter – the globus pallidus, a part of the brain associated with voluntary movement.

Not just grey matter was impacted, however. The results also showed that white matter in the brain – the tissue that relays communication through the organ – was also affected by high body fat, displaying microscopic changes to its structure, although the effects of these alterations aren't clear.

The researchers acknowledge that due to data limitations, their study didn't look at any links with actual cognitive decline in the participants, only brain architecture itself.

Because of that, we can only speculate on what these aspects of grey matter shrinkage might mean in behavioural terms; importantly, the researchers also point out we don't know which way causation runs here.

"Other than obesity influencing brain structure, a reverse direction of associations could also be possible by a neuronal influence on body weight regulation and eating behaviour," the researchers write in their paper.

"Lower grey matter volume of mainly frontal and limbic brain areas in obesity suggest that regulation of eating behaviour could be influenced by altered inhibitory control by lower grey matter volume in these areas and affected signalling pathways of the cortical-limbic tract."

There's still lots to unpack here, including whether, as Dekkers suggests, the kinds of associations we see here might in fact be reversible.

"Future research is needed to evaluate whether stringent weight reduction and treatment of obesity related metabolic disorders also benefit the potential neurologic consequences of obesity," the authors conclude.

The findings are reported in Radiology.