As solid as our planet's crust might feel beneath our feet, we're literally surfing mountains across a churning sea of hot minerals. For years, researchers have struggled to understand what drives the complex movements of Earth's surface layers; now, we might be a little bit closer to the answer.

To determine whether drifting tectonic plates stir the mantle, or the mantle's currents are what moves the crust, scientists have now stepped back to look at the problem in a different light, treating it all as a single system. And it's looking complicated.

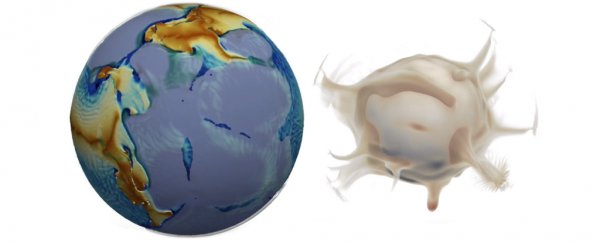

An international team from École Normale Supérieure and the Université Grenoble Alpes in France, and the University of Texas at Austin in the US has come up with fresh new 3D models of an Earth-like world, complete with equations that took a supercomputer nine months to solve.

The results suggest we've been looking at this question the wrong way this whole time. Forget asking whether it's the sinking of a cooling crust that pushes against the mantle, or vice-versa – both play key roles in deforming a planet's surface as it ages.

We've imagined for the better part of a century that Earth's outer coat slips around like a loose suit of armour, its plates clanking together in some parts and pulling apart in others.

Early attempts to describe such a theory of plate tectonics suggested this movement could be largely the result of convection currents in the fluid of hot, pressurised rock we call the mantle as it rises, cools, and sinks.

Since the 1950s we've learned a great deal about how the surface sinks in some parts and rises in others, churning out fresh new rock while melting old crust in a constant conveyer belt of destruction.

Models attempting to describe this process have inevitably run into problems trying to match the dragging and friction forces of grinding plates with the dynamics of a flowing mantle deep below.

"Results point to a prevalence of slab pull force over mantle drag at the base of plates, which suggests that tectonic plates drive mantle flow," the researchers explain in their report.

The picture we get now suggests we're not surfing on a flowing mantle, but sailing, with our continental 'sailboats' whipping up whirlpools in the molten sea below.

If these models suggest the movements of tectonic plates create currents in the mantle, we find ourselves with a chicken-and-egg conundrum of asking how currents in the mantle might push around the plates in the first place.

Metaphors of boats and suits of armour have their limits. To really understand the complex interactions between the crust and mantle we need to stop seeing them as distinct materials, argue the researchers, and come up with better descriptions.

The descriptions the team arrived at allowed them to recreate a planet like ours and watch it evolve over its first 1.5 billion years. By looking at the mantle and crust as gradients of heat and pressure, they could better understand how they each changed.

Their Earth twin revealed a rather complex dance of continent formation, drifting, and mantle flow that shifted over millions of years.

About 20 to 40 percent of the surface, they found, is indeed pulled along by the flowing guts of the planet. But that means as much as 60 percent of the surface drags on the mantle.

These patterns also change over time. The thicker chunks of continental plates are dragged along by deeper currents, until they crunch together into a supercontinent. As the supercontinent fractures and breaks apart, the sinking of plates in turn causes the mantle to flow.

The models suggest there's a lot more going on down there than we can make out from the surface, which has made it challenging to imagine just how the mantle's currents and the crust interact.

So much of what happens deep beneath the surface has grave repercussions for life on the surface.

From earthquakes to volcanoes, to the protective magnetic cage shielding us from blasts of high energy particles from the Sun, we're at the mercy of geology we're still working out.

This research was published in Science Advances.