Scientists have previously suspected supermassive black holes can merge together, and have seen signs of these cosmic collisions on a smaller scale. Now new research backs up the hypothesis – and shows evidence that it could be happening all across the Universe.

Astronomers studying detailed radio maps of jet sources – powerful beams of ionised matter thrown out by black holes – have found a surprisingly high number of scenarios that matched patterns consistent with binary black holes (two black holes orbiting each other).

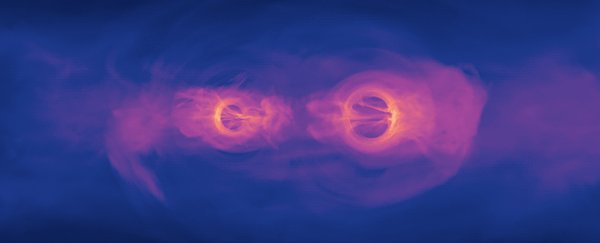

Jet stream radio map. (M. Krause/University of Hertfordshire)

Jet stream radio map. (M. Krause/University of Hertfordshire)

These binaries are likely to lead to mergers on a supermassive scale, the researchers say, with galaxies devouring each other, and the black holes at their centres joining to create even greater forces than before.

These are fundamental ideas about how the Universe works and evolves.

"We have studied the jets in different conditions for a long time with computer simulations," says one of the team, astronomer Martin Krause from the University of Hertfordshire in the UK.

Now, the researchers compared these computer simulations with radio map data gathered from the MERLIN array of telescopes to find signs of precession – apparent alterations in the axis of rotation of the supermassive black holes under observation, suggesting a binary link where two black holes are indeed pulling and pushing each other.

Of the 33 jet sources studied, 24 (73 percent) were consistent with the sort of patterns we'd expect from a binary black hole dance. This could be happening a lot.

"In this first systematic comparison to high-resolution radio maps of the most powerful radio sources, we were astonished to find signatures that were compatible with jet precession in three quarters of the sources," says Krause.

Before we get too carried away, it's worth noting that actually observing these supermassive black hole mergers is going to be very difficult.

It's probably beyond the capabilities of our current technology – but at least the early signs are good.

And as usual in these kind of studies, some assumptions are being made about how to interpret the data: more than one explanation is possible. This is how we can unravel the mysteries of space, one piece of evidence at a time.

First comes the informed hypothesis, then (hopefully) comes the proof – whether that's black holes ejecting matter twice or feeding from a magnetic field.

If the astronomers are right in this case, it could teach us a lot about how galaxies form.

New stars get birthed from cold gas, and hot jet streams stop that from happening – and if those jets are spinning around in pairs rather than fixed in one place, that has consequences for the number of stars a galaxy can produce.

That sort of analysis will have to wait. For now, it seems we might have to adjust our expectations around just how many binary black holes – and subsequent supermassive black hole mergers – there are out there.

"The high fraction of close binary black holes in powerful jet sources might suggest that supermassive black holes in general are very likely to occur as a binary system," the researchers conclude.

The research has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.