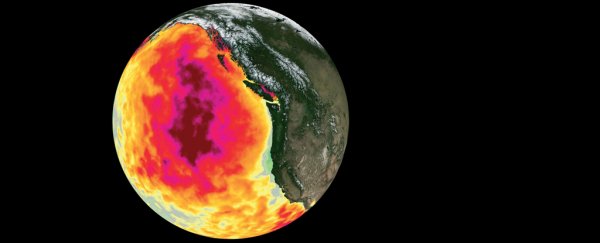

In 2013, a suffocatingly hot blob of water brewed in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of North America. It then decimated marine life.

Thousands of seabirds washed up dead on shores, along with starving baby sea lions. Salmon, krill, and other marine animals vanished as the warmth fuelled a massive toxic algal bloom that also shut down crab fisheries.

Confused summer breeding fish spawned during winter, while lost subtropical species such as swordfish and pyrosomes appeared far outside their normal range. Over 100 million Pacific cod are thought to have perished.

At its peak, parts of this blob reached almost 4 °C above normal water temperatures and the anomalous pocket of heat persisted until 2015.

Since then, more monstrous hot water blobs have formed in oceans around the world - wreaking havoc on ecosystems and fisheries, and setting back decades of efforts to save species like humpback whales, whose populations plummeted by 30 percent. These marine heatwaves have also caused mass coral bleaching, melting sea ice and the release of carbon dioxide from dying seagrass.

Now new evidence suggests that the intensity of these events isn't just fuelled by climate change - it's making the very occurrence of blobs more likely, too.

Environmental physicist Charlotte Laufkötter from the University of Bern in Switzerland and colleagues studied the marine heatwaves recorded between 1981 and 2017. They found the 300 largest events lasted on average 40 days, covered an average of 1.5 million km2 and had a peak temperature of 5 °C.

Focusing on the seven largest, most recent blobs, the researchers calculated how likely each would have been with or without current global warming. Their analysis, which used conservative estimates of risk attributions, found impactful marine heatwaves are now over 20 times more likely because of human induced climate change.

"The frequency, duration, intensity, and cumulative intensity of large marine heatwaves increased during the observational period," the team wrote in their paper.

(NOAA)

(NOAA)

Before our pollutants started messing with Earth's thermostat, such large and intense marine heatwaves occurred only once in a few hundred or even thousand years. The researchers' modelling suggests that once we reach 1.5 °C of global warming, such horrible hot-water events could occur up to every decade at worst; by 3 °C they could become as regular as annually.

They caution these predictions probably won't hold true if warming stabilises at these temperatures, once the ocean has had time to take up and redistribute more of the heat.

"Strongly reduced return periods of large marine heatwaves will likely push marine organisms and ecosystems beyond their thermal limits and stress tolerance, potentially causing irreversible changes," the researchers warn in their paper.

For not only do these hot water blobs have immediate impacts on marine life, but researchers found a huge and ongoing shift in the affected regions' food chain - a reduction of nutrient rich plankton was replaced by nutrient poor gelatinous zooplankton that's likely to have major consequences across the entire food chain. And many reefs that have been impacted will already never recover.

Coho salmon that went to sea during the 'blob years' are noticeably thinner. (NOAA)

Coho salmon that went to sea during the 'blob years' are noticeably thinner. (NOAA)

Laufkötter and team's findings align with other evidence that these devastating marine heatwaves are becoming more typical. A 2018 study showed there was a doubling of marine heatwave days between 1982 and 2016.

"At some point, everywhere might look like what we think of today as an anomaly," said oceanographer Andrew Leising from NOAA, after also analysing recent marine heatwaves. "It wouldn't be anomalous anymore."

This does not bode well for many of the 3 billion humans that rely on our oceans for income and sustenance.

Researchers are developing tools to forecast and track these anomalies, and working on ways to better manage these events with fishery industries.

But the team concludes: "To maintain the existence of resilient and productive marine ecosystems and to prevent many oceanic regions from reaching a continuous, severe heatwave state, global warming needs to be severely limited."

Sadly, when it comes to convincing those with the power to make the required meaningful changes, it really feels like we may as well be trying to tell this all to the blob's fictional namesake.

This research was published in Science.