When you think of the colour scheme sported by the prehistoric world of the dinosaurs, greens and browns typically spring to mind.

But more and more research has shown that millions of years ago, vibrant, vivid colours were everywhere in nature, just like they are today. The latest evidence - 99-million-year-old insects caught in amber with incredible colours of purple, blue, and metallic green.

One of the reasons it's so hard for us to know the colours of prehistoric creatures is due to what's left from them - a fossilised bone can't convey what colour the animal was. But lately, scientists have been working out pigments from fossilised feathers; or, in the case of this latest study, used Burmese amber to peer into the world of ancient colours.

"The type of colour preserved in the amber fossils is called structural colour. It is caused by microscopic structure of the animal's surface," explained palaeontologist Pan Yanhong from the Chinese Academy of Science.

"The surface nanostructure scatters light of specific wavelengths and produces very intense colours. This mechanism is responsible for many of the colours we know from our everyday lives."

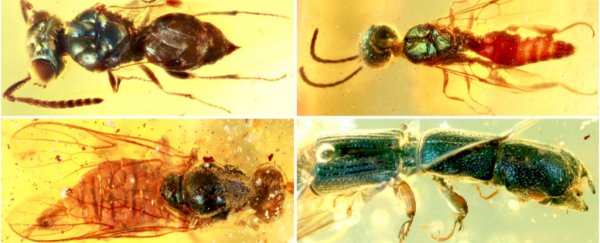

A number of insects studied by the researchers. (Cai et al., PRSB, 2020)

A number of insects studied by the researchers. (Cai et al., PRSB, 2020)

Structural colour is what makes peacock feathers and butterfly scales appear iridescent; in this case, it was created by the outer cuticle of the insect's exoskeleton.

The team collected 35 amber specimens containing ancient insects that also possessed these intense structural colours.

The vast majority of the specimens were either cuckoo wasps (family Chrysididae) or chalcid wasps (part of the superfamily Chalcidoidea). The amber-encased creatures showed off their metallic bluish-green, yellowish-green, purplish-blue, or even vibrant green bodies.

Interestingly enough, the cuckoo wasps in amber (see, for example, the first green insect in the series of images above) were nearly the same colour as the cuckoo wasps that are around today.

A modern cuckoo wasp. (Wasrts/Wikimedia/CC BY 4.0)

A modern cuckoo wasp. (Wasrts/Wikimedia/CC BY 4.0)

"The colour displayed by fossils can often be misleading because fine nanostructures responsible for coloration can be altered during fossilisation. However, the original colour of fossils can be reconstructed using theoretical modelling," the team writes in their paper.

"The calculated reflectance peaks match the observed metallic bluish-green coloration of the mesopleuron of our studied wasp, confirming that extremely fine nanostructures can be preserved in Mesozoic amber."

The team also thinks they have an explanation for why only some amber insect fossils retain the colouration of the animals inside.

After cutting through the exoskeleton of two of the vibrant wasps and one comparatively dull fossil, they found that in the dull sample, the cuticular structures which create the structural colours are damaged. In the colourful fossils, the insects' exoskeletons and the nanostructures that scatter light were still preserved.

While we admire the discoveries, it's important to note the palaeontology community is currently debating whether the scientific information that can be gleaned from these specimens collected and sold in Myanmar is worth the price of the potential human consequences, including the persecution of ethnic minorities.

In the last few years, amber has given us incredible creatures from the Cretaceous. These animals lived nearly 100 million years ago, and findings include the skull of the smallest dinosaur, some tiny frogs, a bird with a weirdly long toe, and many, many more.

The research has been published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.